Robert J. King

THE MULOVSKY EXPEDITION AND CATHERINE II’s NORTH PACIFIC EMPIRE

During the reign of the Empress Catherine II important changes occurred in the sphere of Russia’s external affairs, such as obtaining an outlet to the Black Sea in 1774 and annexation of the Crimea in 1783. Like the other leading European powers, Russia aspired to have the capability to carry out long distance oceanic voyages and to undertake geographical discoveries. With that objective, in April 1787 the Government of Catherine II commissioned Captain of the First Rank Grigory Ivanovich Mulovsky commander of a small squadron destined to carry out a voyage to the North Pacific Ocean including Kamchatka, Japan and the western coasts of America. The principal tasks of the expedition were formulated as being, “securing the safety of long-distance trade and commerce, making useful discoveries and obtaining geographical knowledge”, making ethnographic observations, and the study and collection of descriptions of the islands, shores, bays and harbours neighbouring Kamchatka as far as Japan.

The importance of the intended Mulovsky expedition may be understood within the wider context of the European entry into the Pacific and exploitation of its resources following the breakdown of the Spanish mare clausum regime there in the late eighteenth century. News of James Cook's voyage to the Pacific of 1776 to 1780 led Russia to look at the area in terms of economic and strategic considerations and to increased consciousness of the Pacific's importance.[1] The attempt to organize the Mulovsky expedition was a Russian response to the Cook. Cook’s voyage inspired similar responses from other European powers with maritime pretensions: an attempt was made to organize an Imperial Austrian expedition under the command of William Bolts; there was the French expedition commanded by Jean Galaup de Lapérouse; and the Spanish expedition under Alexandro Malaspina. As a Russian response to the growing presence of the English in the Pacific, the Mulovsky expedition would probably have visited the new English colony at Sydney Cove, New South Wales, some time during 1788.

In July 1787 the London press reported the intention of

the Government of Catherine II of Russia to send out a voyage of discovery

around the Cape of Good Hope to the North Pacific:

A

letter from Petersburgh, dated June 20, says, that

that Government is busily occupied in establishing its power on the Black Sea,

and has likewise formed the project of extending it, if possible, on the other

seas at the extremity of the empire. With this design they have ordered a

frigate of 36 guns and three other vessels to be fitted out, besides a small

squadron, destined particularly to take the soundings and examine the coasts of

China and Japan, and afterwards those of Kamschatka, that new and correct

charts may be made of those coasts, in order to render the navigation of them

more secure, or to procure an exact knowledge of those parts. These vessels

will proceed by the way of the Indian Sea, and will sail directly from

Cronstadt for the Cape of Good Hope. Capt. Maulowsky has been to receive his

instructions from the Empress herself at Kiow [Kiev].[2]

The

Russian initiative took its origin from the activities of other European powers

in the North Pacific, a part of the world that Russia had become accustomed to

regard with an exclusive eye. A Voyage to

the Pacific Ocean, Captain James King's account of the voyage he undertook

under the command of James Cook to the North Pacific (Cook's last voyage), was

published in May 1784. His description of the possibilities of the North

Pacific fur trade attracted wide attention. In particular, his vivid account of

the prices paid at Canton for the sea otter furs the crew had gathered on the

American coast was repeatedly referred to in public discussion:

During our absence, a brisk trade had been carrying on

with the Chinese for the sea-otter furs, which had, every day, been rising in

their value. One of our seamen sold his stock, alone, for eight hundred

dollars; and a few prime skins, which were clean, and had been well preserved,

were sold for one hundred and twenty each. The whole amount of the value, in

specie and goods, that was got for the furs, in both ships, I am confident, did

not fall short of two thousand pounds sterling…When it is remembered that the

furs were at first collected without our having any idea of their real value,

the first two Otter skins we had having been bought for six green glass beads,

the greatest part of them having been worn by the Indians, from whom we

purchased them; that they were afterwards preserved with little care, and

frequently used for bed-clothes, and other purposes, during our cruise to the

North; and that, probably we never received the full value for them in China;

the advantages that might be derived from a voyage to that part of the American

coast, undertaken with commercial views, appear to me of a degree of importance

sufficient to call for the attention of the public...The rage with which our

seamen were possessed to return to Cook's River, and buy another cargo of

skins, to make their fortunes, at one time, was not far off mutiny.[3]

A

mercantile response to the enticing prospects held out by King was not slow to

eventuate. British merchants in Canton and in Indian ports were in a position

to take prompt action in response to the revelation of fortunes to be made from

the trade in sea otter furs. In April 1785, the 60-ton brig

Sea Otter (or Harmon, her previous name) sailed from Macao for the North West

coast under the command of James Hanna. The vessel was chartered by John Henry

Cox, a Canton merchant, on behalf of backers in India and Canton. Hanna made a

most profitable voyage, and his success on the Canton market upon his return

more than fulfilled the promise held out by the experience of the crews of the Resolution and Discovery. Word of this success was sent back to England and

reported in the London press on 21 September 1786:

The Sea Otter, Capt. Hannah, is arrived from King

George's Sound, on the West coast of America, after one of the most prosperous

voyages, perhaps, ever made in so short a time. This brig, which was only 60

tons, and manned with 20 men, was fitted out in April 1785, by Capt.

Mackintosh, of the Contractor, and some other gentlemen in the Company's

service, as an experiment while the Captain is gone to England to procure a

licence from the India Company for the carrying on this trade. Should he

succeed in his application, of which I presume there is but very little doubt,

I am sensible it will insure them a tremendous fortune; you will be astonished

when I tell you, that the whole out-fit, with the vessel, did not cost them

1,000 l. [pounds] and though she was

not more than one month on the coast, the furs she collected were sold at

Canton for upwards of 30,000 l. Had

they had goods to have bartered, and had been two or three months more on the

coast, Captain Hannah assured me he could have collected above 100,000 l. of furs.— The beauty of these furs is

beyond description, and held by the Chinese in the highest estimation: it is

astonishing with what rapidity they purchased them.— Captain Hannah acquainted

me that there were several sent home to England as presents; your friend Sir

Joseph Banks hath two of them sent by this ship, where no doubt you will see

them.— It is astonishing that this business hath not been taken up long before

this directly from England, as there is a full description of it in the

publication you sent me of Capt. Cook's last voyage: it is fully expected that

when the astonishing value of this trade is well known in England, that the

Company will send out some of their China ships to trade for furs on that

coast, and to try to open a trade from Japan for the disposal of them. Should

they be able to accomplish this trade it would be a great acquisition, as it

would procure them vast quantities of silver and gold, and the furs would sell

for 300 per cent. more than they do at China. The

trade is carried on by the Chinese at an amazing advantage.[4]

The Russian Ambassador in London, Count Simon Romanovich

Vorontsov, forwarded this information to State Secretary Pavel A. Soimonov in

St. Petersburg. Together with the information on the success of the Sea Otter’s voyage, Vorontsov forwarded

to Soimonov a proposal from James Trevenen, an unemployed naval lieutenant who

had been with Cook on his last expedition, for a Russian expedition to the

North Pacific. Trevenen referred to Cook’s intention, before his death, of

exploring the coasts of China and Japan and as, ‘to all appearance this project

is no longer thought of here’, he had resolved to

offer his services to the Empress of Russia to undertake the proposed

expedition. The opening of trade to Japan, he thought, gave reason to entertain

the most flattering hopes of changing ‘the useless and uninhabited wastes of

the bay of Awatchka into the flourishing neighbourhood of a commercial city

[Petropavlovsk] which may extend its influence over the whole country of

Kamchatka and produce a revolution throughout the affairs of the eastern world.’[5]

Upon

receipt of the information concerning the voyage of the Sea Otter, Soimonov submitted a memorandum in December 1786, ‘Notes

on Trade and Hunting in the Eastern Ocean’, to Vorontsov’s brother, Count A.R.

Vorontsov, President of the Ministry of Commerce, and to Count Ivan

Grigoryevich Chernyshev, the Naval Minister, warning of the danger posed to the

Russian interests in the ‘Eastern Sea’ by the encroachment of the English

traders:

The sloop Otter sent by their East India Company,

returning from the St. George Channel [Nootka Sound] which lies at about 50º

latitude, brought to Canton bartered soft goods [furs] worth up to 30,000

pounds sterling. Her captain, Macintosh, asserts that if he had been supplied

with goods for trading with the Americans [natives] he could have obtained a

cargo worth up to 100,000 pounds while the outfitting of his vessel cost no

more than 1,000 pounds sterling. On such basis the English already nourish the

hope to extend this trade not only in China but also in Japan and consider it a

source of great potential riches.[6]

A report from Kamchatka

published in St. Petersburg on 19 December 1786 could not have but reinforced

Russian concern about English encroachment:

Accounts are received from Capt. Ismayloff, Governor of Kamtschatka,

that two armed ships, under English colours, from the coast of America, with a

cargo of furs, were put into the island of Metmi [Matsumae, i.e. Yezo, now Hokkaido]; that on their

arrival they were not allowed to land or even traffic for fresh provisions, but

after making the Prince some valuable presents of European articles, they had

entered into a league of friendship with him for the carrying on a traffic with

the Japanese for the disposal of their cargoes, which chiefly consisted of

furs; that before the sloop which brought the intelligence sailed from Metmi,

they had made several voyages to the Coast of Japan, and met with great

success; that they were preparing to leave some of their people on the island,

to whom the Prince had promised protection; and had actually betrothed one of

his daughters to the supercargo who was to be left on the island as commander

of the party, for the carrying on a correspondence with the Japanese and Kurile

islands.[7]

This

referred to the Lark, under William

Peters, and the Sea Otter, under William Tipping. The Lark left Macao under the command of Peters in July 1786. As

stated by Soimonov, the English merchants were interested in extending their

trade to Japan, and Peters was instructed to make his passage between Japan and

Korea, and to examine the islands to the north of Japan.[8]

After calling at Matsumae (Yezo) and Petropavlovsk, he was lost with his vessel

on Mednyy Island, one of the Commander Islands. The Calcutta Gazette of 4 April 1793 reported:

The

Phoenix, Captain Moore, just returned from the N.W. Coast of America, brings

the first substantiated accounts which we have heard of the loss of the Lark,

Captain Peters, which vessel was fitted out from this port some years ago. The

Lark was lost on Beering's Island off Kamscatca [in fact, on the neighbouring

Mednoy, or Copper Island], and several of the crew got on shore; but owing to

the hardships they underwent from the inclemency of the climate, and want of

necessaries, only four survived, who were relieved by a Russian vessel, which

carried them to Siberia, where they have met with the most humane and attentive

treatment from the Russians—they are two Portugeze and two lascars, and are

still residing at Irkush in Siberia.[9]

The Sea Otter, under Tipping, sailed from

Calcutta on 1 February 1786 and, according to his journal, "made his

passage between Korea and Japan; had communication with the inhabitants of the

latter; and had visited some of the islands to the northeast of Japan".[10]

The Sea Otter was lost during her

return voyage from the North West Coast of America, but before that Tipping

spoke with James Strange, another fur trader, when their tracks crossed near

Prince William Sound on 5 September 1786, and showed him his journal. The

Russian fur trader Grigory I. Shelikhov went to Petropavlovsk to meet Peters

and bought goods from him, and made an agreement to buy more goods from him on

future visits. Shelikhov subsequently made a report to the Governor-General at

Irkutsk, in which he warned that ‘it may be seen that foreign nations that are

not contiguous to our possessions and have not the slightest rights to this sea

are endeavouring to reap the great benefits that properly belong to the Russian

throne and to its subjects’.[11]

Trevenen’s

proposal, and the memorandum from Soimonov caused A.P. Vorontsov and his

colleague, Count A.A. Bezborodko to advise the Empress in a memorandum dated 22

December 1786/1 January 1787[12] to declare to the other European powers that the

Kuriles, Aleutians and North West Coast of America belonged to Russia by right

of discovery and that no other nation could therefore sail to or settle there.

To enforce this claim, they recommended the sending of ‘two armed ships, on the

model of those used by Captain Cook, as well as two armed naval sloops, or

other vessels’, from the Baltic around the Cape of Good Hope and, with stops at

Batavia or Canton, to Kamchatka and beyond, where they would defend Russian

enterprise and dominion, make more discoveries, and perfect existing charts. One

of the ships would examine the Kurile Islands while the other would explore the

Aleutians and the American coast as far East as Prince William Sound. Vorontsov

and Bezborodko supported a recommendation by Soimonov that a new port be

founded at the mouth of the Uda River, which would be better placed than

Okhotsk to serve as a base for Russian sovereignty in the region, and they

proposed that the expedition be assigned this task.[13]

The

Russian Court had received on a previous occasion a proposal to send an

expedition to the North West Coast of America. In 1781-82, inspired by what he

had learned of the findings of Cook’s final voyage in the North Pacific, the

merchant adventurer William Bolts, who since 1776 had been trading to India and

China under an Imperial charter, had developed a plan for the Austrian Emperor

Joseph II for a voyage of circumnavigation with political, scientific and

commercial objects that would have included exploration and colonization of the

North West Coast of America and the Kurile Islands.[14]

It was to have been carried out by Bolts in command of a ship belonging to the

Imperial Asiatic Society of Trieste. Nathaniel

Portlock, who led an English fur-trading expedition to the North West Coast in

1786, claimed that Hanna’s voyage owed its inspiration to this scheme of Bolts.

The Sea Otter had been chartered in

Canton by John Reid and John Henry

Cox who headed a consortium of British merchants. John Reid had been set

up at Canton in 1779 as Austrian consul and agent of William Bolts’s Imperial

East India Company of Trieste.[15]

Reid had been at Canton in November-December 1779 when Cook’s ships, Discovery and Resolution, under the command of James King, had called there and

caused a sensation because of the success their crews had in selling the sea

otter pelts they had obtained for

trinkets on the North West American coast in the course of the great navigator’s third expedition.[16]

Reid had presumably reported this to Bolts, who immediately grasped the

possibilities of the new branch of commerce opened up by Cook’s voyage. Portlock wrote in his account of the voyage:

As early indeed as 1781, a well-known individual, Mr.

Bolts, attempted an adventure to the North Pacific Ocean from the bottom of the

Adriatic, under the emperor’s flag; but this feeble effort of an imprudent man

failed prematurely, owing to causes which have not yet been sufficiently

explained. The project of Bolts appears to have been early adopted by the

British subjects who are settled in Asia….And a brig of sixty tons, with twenty

men, under the command of James Hanna, was, in pursuit of this flattering

object, dispatched from the river of Canton in April 1785.[17]

When

plans for an Austrian venture fell through in late 1782, the Emperor consented

in November 1782 to a request from

Bolts to place his proposal before the Court of Catherine II of Russia, then on

friendly terms with Austria.[18]

In his petition to the Emperor, Bolts said that the expedition would sail from

Trieste under the Russian flag.[19]

He sent a letter dated 17 December 1782 to the Russian Vice-Chancellor Ivan

Andreyevich Ostermann, explaining his proposal. The details of his plan were

set out in a separate document, but it appears to have been the same as set out

in the proposal he subsequently put to the French Court in 1785. He outlined to

Ostermann his plan to send his ship the Cobenzell

from Trieste to the North West Coast of America by way of Cape Horn under

naturalized English officers who had made the voyage with Captain Cook, of

whose charts and plans Bolts had obtained copies. The North West Coast should

be claimed for Russia, and this would enable a most advantageous commerce

between that region and Kamchatka, all the coasts of Asia and as far as East

Africa, as well as all the intermediate islands along the way. He also held out

the prospect of discovering ‘the communication strongly suspected to exist

between Hudson’s Bay and the Pacific’ in the region to taken possession of for

the Empress. Some of the Pacific islands along the way could be suitable for sugar

plantations to provide Russia with a direct supply of that commodity. For the

conduct of this enterprise, Bolts required an advance of 150,000 roubles,

against which as security he offered the Cobenzell

and her cargo, then at Trieste preparing for her voyage to India and China.[20]

When

the Russians proved unresponsive, probably because Trieste was an unacceptable

home port for a Russian expedition, Bolts put his plan before the French Court

of Joseph’s brother-in-law, Louis XVI, which adopted the concept (though not

its author) leading to the sending out of the Lapérouse expedition in July

1785.[21]

In September 1787, this expedition called at Petropavlovsk, Kamchatka, from

whence Lapérouse’s journal and other reports were carried back to Versailles

over land through Siberia and Russia, including St. Petersburg, by Barthélemy de Lesseps.[22]

From

the time she had first learned of it, Catherine had regarded the expedition of

Lapérouse as a threat to Russian interests in the North Pacific.[23] The Spanish ambassador in St. Petersburg reported to

Madrid in February 1786:

I

have information on how greatly this Court suspects that the French expedition

under the command of Mr. de la Peyrouse has the aim of taking possession of a

port not far from Kamchatka, where the river to which the English explorer Cook

put his name empties into the sea. It is believed here that from this place

France will be able to carry on a most profitable trade in furs, there being a

great demand for this kind of goods in Japan, China and in other parts on the

coasts of Asia. This has given rise to talk of making another expedition by sea

from Archangel to the same port, following the course of the French frigates to

observe them and to make sure of arriving before them; but as this thought has

not been put into effect during the course of the last year, I suppose it to

have been set aside, but the expedition by land which has been sent out from

here and their views on the territorial boundaries of China surely have for

their main object the securing of the said branch of commerce.[24]

Perhaps

Catherine recalled the advantages William Bolts had held out from such an

enterprise, which had obviously found a ready audience at the French Court.

Within ten weeks of the sailing of the Lapérouse

expedition, orders were drawn up in St. Petersburg for a ‘geographical and

astronomical’ expedition to easternmost Siberia, the Aleutians and Alaska, commanded by Captain Joseph

Billings. This was reported in The St.

Petersburg Gazette of 28 June

1785:

H.M.

the Czarina has ordered an enterprise directed at removing the doubt that still

remains concerning the extent and position of the coasts of eastern Siberia,

and of those of that part of the American Continent opposite them, as well as

of the Islands situated in the intermediate seas. The Officer, to whom this

charge has been committed, is Mr. Billings, companion of Captain Cook in his

last voyage. He has orders to go overland to eastern Siberia, to determine the

true position of the River Kolyma, and of the coasts of the country inhabited

by the Chukchis, who have voluntarily submitted themselves to the sceptre of

Catherine II. Afterwards he will embark at Okhotsk for the purpose of

completing the chart of the Islands tributary to Russia, and maps of the ports

or harbours of America, whither go the vessels from Okhotsk for trafficking in

furs; and finally to fill in the gaps that remain from the former navigators

concerning various coasts and Islands of the eastern Ocean. Six years will be

spent on this expedition; and the commander, who will be accompanied by an able

Botanist, goes with all the aids and instruments proper for perfecting

Geography and the physical knowledge in general of the terraqueous globe.[25]

The

arrival of the French expedition in the North Pacific, and even more the

encroachments of English (and Spanish) voyagers into that region which the

Russians regarded with a proprietary eye, demanded that Billings’s scientific

survey be complemented by naval force that could occupy and defend Russian sovereignty,

and plans were drawn up for an expedition of five ships, under the command of

Captain Grigory Ivanovich Mulovsky (Григорiй Ивановичъ

Муловскiй), to explore the North West coast of America and claim

it for Russia, and to open trade with Japan.[26]

The Empress’s ukase authorizing the expedition was issued on 22 December 1786

(2 January 1787 new style), and specifically stated that it was being sent out

‘for the protection of our rights to the lands discovered by Russian

navigators’, because of ‘the attempt on the part of English merchants to trade

and hunt in the Eastern Sea’.[27]

Mulovsky

was the natural son of the Naval Minister, Count Ivan Grigoryevich Chernyshev

(hence he bore his mother’s surname), and was aged twenty-nine. He had been

trained in the British Navy, spoke four languages (he had served a period in

the British navy, and George Forster said he spoke English like a born

Englishman) and was considered the fleet’s best officer. He had graduated from

the Naval Academy in 1772, had commanded a 74-gun ship in the Mediterranean in

1782, and become Captain of the First Rank in 1784. His name was mentioned in a report in the Gazeta de Madrid of 17 December1782,

which stated that on 11 November the Russian 74-gun ship David, under her Captain, ‘Mr. Molosky’, had anchored in the port

of Leghorn, and that the ship was one of a squadron that would spend the winter

in the Mediterranean. The same journal recorded the

departure on 10 December of the David,

commanded by ‘Capitan Morosquí’, for Naples, where she was to take on board

official gifts from the King of Sicily.

Academician

Peter Pallas, Russia’s foremost naturalist, drew up a memorandum of advice for

the expedition. As the expedition’s naturalist and official chronicler, Pallas recommended George Forster, who

had accompanied his father, Johann Reinhold Forster, on James Cook's expedition

of 1772-1775 and who was currently Professor

of Natural History at the University of Vilna (Vilnius, in Polish ruled

Lithuania).[28]

Pallas recommended that the expedition found new settlements: on Sakhalin as a

base for Russian power in the region; and on Urup, one of the Kuriles, which

would ‘serve as a focus for direct trade by sea with China and Japan’. Urup was

also favoured by William Bolts as the place for a settlement in his plan for exploration

and trade with China and Japan, and perhaps

Pallas was influenced by this.[29]

Bolts drew on G.F. Muller’s Voyages

& Découvertes faites par les Russes (Amsterdam, 1766) which contained a

list and description of the Kurile islands, including

Urup whose people were said to trade with the Japanese but were not under their

control, and presumably Pallas also relied

on this source.[30]

In fact, a small Russian presence had

been established on Urup by the fur trader Ivan Chernyi in 1768, acting on

instructions from the Governor of Siberia. During the 1770s it was the base for

attempts to establish trade with the Japanese on Yezo (Hokkaido) which came to

an end when it was destroyed by a tsunami in June 1780.[31]

The attractions of the Kuriles, presumed to

be independent of Russia and Japan, had been described by James King in A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean:

Should we be so fortunate as to find in these islands

any safe and commodious harbours, we conceived they might be of importance,

either as places of shelter for any future navigators.…or

as the means of opening a comercial intercourse among the neighbouring

dominions of the two empires [Russia and Japan].[32]

In

addition to the four naval ships proposed for the expedition by Vorontsov and

Bezborodko and authorized by the Imperial ukase of 22 December 1786/2 January

1787, Pallas recommended a transport ship be added to the squadron to carry all

the supplies directly to Okhotsk. This was accepted, and the ships comprising

the expedition were the flagship, Kholmogor (600 tons, 38 guns, 169 men),

the Solovki (530 tons, 20 guns, 154

men), the Sokol (450 tons, 16 guns,

111 men), Turukhtan (450 tons, 16

guns, 111 men) and the smaller transport Smelyi (10 guns, 91 men).

James Trevenen was called to St. Petersburg to take

command of one of the ships of the expedition. The Empress’s instructions were

for the expedition to rendezvous in Portsmouth, England, thence to proceed to

the Cape of Good Hope by way of Lisbon,

Madeira and Rio de Janeiro. From the Cape, the commander was given the

choice of proceeding to the North Pacific by either the Straits of Malacca or

the Sunda Strait and Manila, Formosa or Canton, or by the South of New Holland,

the Friendly and Society Islands and Hawaii. He was allowed discretion to sail

to the English colony at Botany Bay in New Holland if the ships needed to

repair damage or if circumstances required it.[33] After arriving off the northern

coast of Japan, Mulovsky was to attempt to obtain fresh provisions from the

coastal residents. He was also ‘not to miss the slightest opportunity to obtain

the most reliable information on that country, especially the northern part and

the large islands lying near its northern margin’. As well, ‘in all cases the

Japanese and Kurilians living on the nearest islands are to be treated in a

friendly manner, and the establishment of trade is to be attempted’. The

expedition was then to split into three detachments: the Smelyi transport was to go directly to Petropavlovsk to deliver

provisions there; two ships were to investigate thoroughly the Kurile islands,

the Japanese territories of Matsumae and Yezo (i.e. Hokkaido), Sakhalin and the Amur estuary as well as the

Shantar Islands, while the remaining two ships, including the Kholmogor under the command of Mulovsky,

were to proceed to the North West American coast, between 40º and 50º North.

The

detachment sent to the Kuriles was to circumnavigate the archipelago and

describe all the islands, chart them accurately, and take formal possession of

them for Russia by posting markers and burying medals with inscriptions in the

Russian and Latin languages. It was also to examine the coasts, bays and

harbours of the islands and make a record of their resources, particularly

those of Urup, with a view to finding the best site for a settlement with

arable land, fresh water, timber for building and ship construction, and a good

port. Time and wind permitting, a search was to be made for any large and

unknown lands to the East of the Kuriles and Japan, the legendary Staten and

Company (or Da Gama) Lands. The island of Sakhalin was to be sailed around and

described, and its resources and inhabitants reported on. The expedition was to

investigate mouths of the Amur and Uda rivers as well as the Shantar Islands

which lay at the mouth of the Uda, with a view to establishing a new port

there, as had been recommended by State Secretary Soimonov. The ships were then

to sail first to Okhotsk for repairs and supplies and then to Petropavlovsk to

rendezvous with Mulovsky’s detachment returning from America.

The American detachment under

Mulovsky himself was to proceed to ‘the St. George Sound or Nootka Haven

discovered by Captain Cook’, which was to be explored, and it was to

ascertained if the English or some other European power had established an

outpost there or were preparing to do so: ‘From this locality you are to

proceed along the American coast to that part thereof which was discovered by

Russian Captains Chirikov and Bering and you are to take possession for the

Russian State of that coast from the harbour of Nootka to the point where

Chirikov’s discovery begins, if no other State is occupying it’.[34]

In any case, formal possession was to be taken of the coast and islands to the

North of that point. However, the Aleutian Islands and the coast north of the

Alaska Peninsula were not to be explored, that task being left to the expedition

commanded by Captain Joseph Billings. If any foreign vessel had anchored in

Prince William Sound or Cook Inlet, it was to be removed, by force if

necessary, and any foreign settlements were to be destroyed and all markers

removed. Mulovsky’s ships were to proceed along the southern coasts of the

Aleutians to rejoin the rest of the squadron at Petropavlovsk. There he was to

assist Billings, if his expedition had not yet departed, by lending him one or

two ships for surveying the northern coasts of the Aleutians and the American

coast as far north as Cape Rodney, at 64º30' North and, time, wind and other

circumstances permitting, as far south as Cape Blanco, at 42º50' North. The

expedition was to spend the winter either on the North West Coast, at Hawaii or

at Petropavlovsk.

The main object of the whole expedition was, according to Mulovsky’s instructions, ‘barring foreigners from sharing in or dividing the fur trade with Russian subjects on the islands, coasts and lands discovered by Russian navigators and rightfully belonging to Russia’. The expedition was to take possession of lands not subject to any other power by raising the Russian flag, affixing a medal to a cross or an inscribed post raised on a promontory some distance from the shore, and putting one copper and one silver coin in a tarred stone vessel and an inscription in Russian and Latin in a tarred bottle and burying them in the ground; or a medal was to be affixed to a large raised post or to a boulder. Native people were to be treated without resort to force, if at all possible, and given small presents. All journals were to be surrendered to the Admiralty upon the expedition’s return to Kronstadt.

Spain’s Ambassador to St.

Petersburg, Pedro Normande, advised in February 1787 that news had been

received in Russia of an English trading vessel bringing sea otter skins to

China at immense profit, from ‘the coasts of America that face Kamchatka, that

are a continuation of those of California’ (a reference to the news of Hanna’s

voyage). This had aroused the interest of the Empress, but great care was being

taken to hide all signs of official concern. Normande wrote that Captain

‘Moloski’, natural son of Count Ivan Chernychev, Minister of the Marine, had

been chosen to command a squadron of four men-of-war to be sent to Kamchatka to

protect Russian interests. Professor Pallas of the St. Petersburg Academy had

been requested to join Mulovsky in drawing up instructions and plans for the

voyage. Meetings at the Admiralty with a secretary of the Empress’s cabinet had

resulted in an official proclamation, plans and maps for Mulovsky. Normande had

discovered that Catherine and her ministers were contemplating a declaration of

Russian sovereignty over all of North America from Mount St. Elias eastward to

the neighbourhood of Hudson’s Bay. This was a region where the Russians deemed

they had primacy of discovery and where some of the inhabitants had already

submitted to Russian rule. Announcement of this sovereignty would be

communicated to other European powers, declaring that Mulovsky’s expedition was

to secure those possessions and defend them against other nations seeking to

make settlements there. The two frigates and two transports would sail by way

of the Cape of Good Hope and join the expedition led by Joseph Billings at

Okhotsk.[35]

Normande’s report was read with

concern in Madrid, where the Government had already at the end of January 1787

sent orders to Mexico for a pair of ships to go to the North West coast to

investigate the extent of Russian advance.[36]

This expedition left the port of San Blas in

Mexico in March 1788, and upon reaching the island of Unalaska in July 1788

learned of the Russian intention to colonize Nootka from the head of the

Russian fur trading settlement there. This man, Potap Kuzmich Zaikov, told the

visiting Spanish commander, Esteban José Martínez, that ‘the next year he

expected two frigates from Kamchatka which, together with a schooner, would go

to settle the port of Nootka to block English trade’. In an apparent reference

to Hanna’s voyage, he said ‘his Government intended taking this action because

an English trading vessel had come to Canton from Nootka in 1785 loaded with a

variety of furs, and its captain had claimed that the English had a right to

trade and possess land along that coast because of the discoveries of Captain

Cook’.[37]

Communication between the Russian and Spanish parties was facilitated by the

pilot with the Spanish ships, Istvan (or Esteban) Mandofia, a native of Ragusa

(Dubrovnik), whose own language proved equal to the task of interpreter,

although he was “very hard to understand”.[38]

The official Spanish account of Martinez’s voyage published in the press

said disarmingly:

Mr. Martinez investigated the

Shumagin islands and many others unknown to Captain Cook, stopping afterwards

at Unalaska, where he was received very cordially by the Russian Commissar, Mr.

Saicost Potap Cusmich, who commanded the colony, where there were 70 Russians

serving and one galliot. The Spanish Navigator, after having stayed a month at Unalaska, set sail and returned to the

port of San Blas, by way of Monterey and the Santa Barbara Channel, without

touching the coast at Nootka where the Russians had no settlement. The fruit of

this expedition has been to dissipate the unease there had been on the subject

of the pretended hostility of the Russians, of whom we have had proofs, on the

contrary, of the most generous hospitality.[39]

This was published at the very moment when Martinez

had returned to fortify Nootka to prevent its occupation by the Russians, the

English or anyone else. The news Martínez brought from Unalaska, confirming the intelligence

provided by Ambassador Normandez from St. Petersburg, prompted the Viceroy of

Mexico to send him back to Nootka immediately to occupy the port, and the

Spanish home government in Madrid was stimulated to send a full-scale expedition from Spain to the Pacific.[40] Commanded by Alexandro Malaspina, it left

Cadiz at the end of July 1789 with among its

tasks that of making an investigation of any Russian settlements on the North

West coast of America.

Meanwhile,

in June 1787, Mulovsky made a visit to George

Forster at his residence at the University

of Vilna and invited him to join the expedition as naturalist and

official chronicler.[41]

Full of enthusiasm, Forster wrote to his friend, Samuel Thomas Soemmerring,

inviting him to join the expedition as surgeon, and outlining its proposed

itinerary:

Still I myself do not quite dare to abandon

the sweet intoxication of the idea that we both, united again in a way which

exceeds our most ardent desires, entered jointly on such an active course,

working hand in hand with each other, taking equal care for fame and fortune,

will visit England, Lisbon, Madeira, Brazil, the Cape of Good Hope, New

Holland, New Zealand, the Friendly, Society and Sandwich Islands, the Coast of

America, Kurile Islands, Japan and China—and

everywhere our zeal for Science will be left unhindered![42]

Soemmerring declined the invitation, leaving the way

open for the

Bohemian, Thaddaeus Haenke, to join the

intended Russian expedition as Forster’s

assistant, as Haenke explained in a letter to a

friend:

I

must tell you before anyone else, that I have the greatest hopes of making the

voyage round the world with Forster, the one which the Empress of Russia will

send out over the coming years and which, on Jacquin’s own recommendation and

with a considerable salary, I will accompany as Botanist… at the beginning of

March 1788, we will sail from England where the ships of the expedition lie at

anchor, southward into the great, wide world.[43]

Forster explained in a letter of 6 August 1787 to his publisher:

The

voyage goes in March 1788 from England (whither the ships will go in September

from Petersburg) by the Cape to New Holland, New Zealand, Otaheiti, the

Sandwich Islands, the coast of North America and from Japan to Kamchatka and

the neighbouring areas, but only to the South of the Bering Strait. The Empress

has given the Captain carte blanche, and spared no expense.[44]

The

London newspaper, The Daily Universal

Register, of 21 September 1787, carried a report from Hamburg dated 24

August, saying that:

The

Empress of Russia has given orders for a voyage to the East Indies to be set on

foot. The object of this expedition is a commercial one to that part of the

world. There will be on board of this fleet an

historiographer, an astronomer, a botanist, and a delineator. We are assured, that Professor Forster, of Wilna, is to be the

historiographer.[45]

As

the Mulovsky expedition had been organized because of Russian concern with the

growing presence of the English in the Pacific, it would probably have visited

the new English colony at Sydney Cove, New South Wales, some

time during 1788. The preparations for the Botany Bay expedition were widely

reported in the English and European press in late 1786. George Forster

expected the Mulovsky expedition to visit New Holland, and in his article, ‘Neuholland, und die brittische Colonie in Botany‑Bay’

(written in November 1786 and published

in the Allgemeines historisches

Taschenbuch…für 1787) he wrote that New Holland was ‘the future homeland of

a new civilized society which, however mean its beginning may seem to be,

nevertheless promises within a short time to become very important’.[46] In his biography of

James Cook, written about the same time, he said: ‘New Holland, considered as a

centre of trade, appears to be favourably situated for linking India and

America and, as it were, for maintaining dominance over the East Asian

archipelagoes’.[47] The Lapérouse

expedition, having received instructions during its call at Petropavlovsk to

investigate the newly-settled English colony, did so in January-February 1788,

and the Malaspina expedition undertook a close examination in March-April 1793;

it is reasonable to expect the Russian government would also have wanted to

obtain first hand intelligence on the colony.

Even as Mulovsky completed his preparations, war clouds were gathering. Catherine’s ambitions to dismember the Ottoman Empire and to see her grandson Constantine installed on the throne at Constantinople brought the reaction that might have been expected from the Turkish Kaisar, who also claimed to be heir to the throne of the Caesars. The impositions of the 1774 Treaty of Kuchuk Kainardji and Catherine’s annexation of the Crimea nine years later provided sufficient provocations, and on 15 August 1787 the Kaisar placed the Russian ambassador in Constantinople under confinement, while his army commenced an attack on the Russian fortress of Kinburn at the mouth of the Dnieper. Nevertheless, preparations for the expedition continued up to the last moment. A report from St. Petersburg of 20 October 1787 said that:

Mr.

Maulofsky, commander of the squadron destined for the Indies and coast of

Kamtschatka, advised yesterday that he stood ready to make sail. He had

provisions for three years, and officers and Marines had been embarked. It was

believed by others that the departure of this detachment had been suspended in

favour of another destination.[48]

A report of similar

date carried in The Whitehall Evening

Post of 6 December 1787 said:

From

Petersburgh we also hear, that (even in the midst of “wars, and rumours of

wars”) Catherine is determined to persevere in her grand object of CIRCUMNAVIGATION. For

this purpose, the squadron destined for the Indies, and particularly for the

coast of Kamschatka, is ready, or nearly ready, to sail, after having laid in provisions for three years.

When it became clear that the Swedish King, Gustaf III,

was seeking to take advantage of Russia’s embarrassment on the southern front

to gain redress of his own grievances in the Eastern Baltic, all of Russia’s

naval resources were required to meet the crisis. Russian naval forces were

also required for operations against the Ottoman Turks in the Mediterranean and

Aegean. The Empress’s ukase cancelling the expedition was issued on 28

October/8 November 1787. The Whitehall

Evening Post of 27 December 1787 carried news from St. Petersburg dated the

preceding 20 November, which said:

Every

disposition making throughout the wide-extended States of our august Sovereign

announces a most obstinate war against the Turks. To support it without

burthening her subjects too much, her Imperial Majesty has recourse to

oeconomy.... The same principle has occasioned the intended expedition to

Kamschatka to be laid aside, orders having been sent to pay off and disarm the

vessels which had been destined for that service.[49]

John

Cadman Etches, a London shipping merchant with good connections in Russia and

with the British Government, and who was one of those involved in the attempt to

establish a trade in furs from the North West Coast of America, published a

description in June 1790 of his understanding of James Trevenen’s proposed

expedition:

So sensible was the Empress of Russia of the importance of this trade, that five

sail of large frigates, armed en flute,

were two years ago equipped at St. Petersburgh, and furnished with every kind

of stores, for the formation of settlements on the north-west coast, and on the

opposite coasts of Asia, for establishing a complete Marine Yard for Ship

building, and for prosecuting a regular system of commerce, on the most

extensive scale, throughout the great Pacific. The equipment was made under the

direction of Captain Trevannon, a lieutenant in the British Navy, and a

favourite officer of the late Captain Cook, whom he accompanied in his last

voyage. This naval expedition, when ready to depart, was frustrated by the

rupture with Sweden… Captain Trevannon was to have acted in concert with a land

expedition, of similar importance and purport, under the command of Captain

Billens, another of Captain Cook’s scholars, who was accompanied by 1500

attendants, and assistants, consisting of the most select mechanicks, artificers,

&c. assembled from all parts of Europe, and who are now, and have been

during the last four years, occupied in surveying the eastern coast, and large

rivers of Asia.[50]

Some of the resources assembled for

the expedition were taken to Okhotsk for the use of Joseph Billings, who was

also assigned some of Mulovsky’s tasks. The Billings expedition, too, was

almost cancelled: a courier from St. Petersburg reached Billings in Okhotsk in

September 1788 with orders for him to return to St. Petersburg if he had not

already left Okhotsk or was not on the point of sailing from thence.[51]

Billings, however, was ready and did proceed with his expedition. By that time

he had already completed the first of his voyages, which The St. Petersburg Gazette

of 1 February 1788 reported:

The

Court has received news of Mr. Beling, the English officer charged a year ago

by the Empress with examining the coasts of the Frozen Ocean, as far as the

eastern and northern extremities of Asia. After having successfully crossed the

whole of Siberia this intrepid traveller constructed a ship proper for this

hazardous voyage. He embarked in it down the Kolyma, and in the month of May

last year debouched from that river to examine, following the coast, the cape

where Captain Cook put an end to his exploration, and whose location he

indicated at great variance with respect to that of the Russian voyagers before

him. If the ice permits, which is not known, the bold enterprise of Mr. Beling

proposes to double Cape Chukchi, and return to Kamchatka.[52]

The

St. Petersburg Gazette of 31 March

1788 further reported on the Billings expedition:

The

Ministry has received news of the expedition made by order of the Empress to

the seas that bathe the N.E. part of Siberia. Captain Belligas, the Commander,

has already left the Kolyma, according to the most recent advice from as late

as July 1787. The boats in which he should have embarked on the Lena being

found not to be ready, as was proposed, to proceed from thence as far as the

Frozen Ocean, he has undertaken his voyage from the Kolyma, thereby shortening

his journey by a year, and being now more easily within reach of the point of

Asia which extends to the N.E., than he would have been by going from the Lena

to that part of the Northern Ocean.[53]

The

St. Petersburg Gazette of 13 April

1792 reported:

The

Ministry has received news from Captain Billings, charged with prosecuting the

Russian discoveries in the Pacific. During the year 1790 this navigator sailed

along the Kuriles and Aleutians, where he found several new plants very useful

for human food; and taking advantage of this useful discovery, he made a

collection of them to test their cultivation in some region of our widespread

dominions.[54]

Meanwhile, the Russo-Swedish war

proceeded at enormous cost to both sides, St. Petersburg itself coming under

danger of capture at one stage. Both Mulovsky and Trevenen gave distinguished

service in the conflict, each surviving several battles before falling in

action. The

Gentleman’s Magazine for

September 1789 carried a Russian report of the death of Mulovsky during the

Battle of Oeland (or Bornholm, as the battle took place in the waters between

the two islands) of 26 July 1789 (15 July in the Julian calendar used then in

Russia):

M. de Moulofsky, who commanded the leading ship of M.

Spiridoff’s division, made incredible efforts to approach the enemy, and had

got a little nearer, as did also five other ships; they sustained the enemy’s

fire till eight o’clock in the evening, with little damage… The Russians have

suffered an inexpressible loss in their brave Captain Moulofsky, who was

wounded by a random shot almost at the beginning of the action; and about three

quarters of an hour after he expired, bravely animating his crew.[55]

James Trevenen’s death in the Battle of Vyborg, 4 July 1790, was reported in the English press:

Letters from Petersburgh say, that in the late naval engagement the Russians lost

four of their British Captains, viz. Commodore Trevenen, a Lieutenant in our

navy, and a pupil of the immortal Cook. Mr. Trevenen went out to Russia, at the

particular request of the Empress, to take the command of a squadron destined

for a voyage of discovery. On the war with the Turks this design was postponed;

and Mr. Trevenen was offered a line of battle ship, and had since received the

most honourable marks of the Empress’s favour.[56]

The

newspaper report indicated that Trevenen was to have had command of a separate

expedition to that of Mulovsky, though complementary to it. The St. Petersburg

correspondent of the Edinburgh journal, The

Bee, wrote: “Public report said…that the commander, captain Molofsky was to

conduct the division of the little squadron by the way of the Cape of Good

Hope, whilst the captain of the second rank, Traveneon…was to take charge of

the other, by the more dangerous route of Cape Horn”.[57] The British Ambassador at St. Petersburg, Charles

Whitworth, wrote to Foreign Secretary Lord Grenville in October 1791:

Two small squadrons were actually equipped at Cronstadt, and ready to sail for Kamtschatka the very moment the war with Sweden broke out. The one was

commanded by Captain Travanion, an Englishman who had been with Captain Cook,

and was to have gone round Cape Horn, the other by Captain Mulofskoi (a natural

son of Count Iwan Chernicky and an excellent officer formed in the English

Navy) who was to have gone round the Cape of Good Hope.… These two commanders

are since dead.[58]

Whitworth

reported that ‘the Empress was much dissatisfied with the English having a

settlement at Nootky Sound’. Whitworth subsequently wrote to Grenville on 18 May 1792 and, after

referring to the abandoned Mulovsky/Trevenen expedition, said the Russians

"certainly build much on the advantages which they expect to derive from

[Japan], and they consider Great Britain as the only Power capable of thwarting

them".[59]

Subsequently, in June 1792 a Russian expedition under Lieutenant Adam Laxman

sailed from Okhotsk to Nemuro in Yezo with the aim (which proved unsuccessful)

of opening relations with Japan. Lloyd’s

Evening Post of 26 April 1794 reported:

A new channel of commerce has been proposed between the

Japanese and the Russians, by a person from Japan who was shipwrecked on the

Russian coast some years since, but returned home with the son of the Professor

Laksman. He [Laksman] is now charged with a kind of treaty to the Japanese,

promising to send a ship to Russia every year; but the want of ship-timber in

Kamschatka is supposed to be a drawback upon this undertaking.

The Japanese castaway referred

to in the newspaper report was the shipwrecked merchant, Daikokuya Kodaiyu ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() , who had been met in Nizhni Kamchatsk

by Barthélemy de Lesseps, the interpreter with the Lapérouse

expedition, who was conveying the journal of Lapérouse from Petropavlovsk to

Paris. De

Lesseps described him in his subsequent book, published in

translation in London in 1790 as Travels in Kamchatka (pp.208-17). British Secretary of

State William Grenville wrote to Whitworth

enquiring as to whether Daikokuya could be recruited as an interpreter for

the embassy that was being organized to be sent to China and Japan

under

George Macartney.[60] The Russians prevented any

access to Daikokuya by Whitworth when he was brought to St.

Petersburg, and used him themselves as an interpreter in 1792 during the expedition to

Japan led by Adam Laxman,

as reported in

Lloyd's Evening-Post.

, who had been met in Nizhni Kamchatsk

by Barthélemy de Lesseps, the interpreter with the Lapérouse

expedition, who was conveying the journal of Lapérouse from Petropavlovsk to

Paris. De

Lesseps described him in his subsequent book, published in

translation in London in 1790 as Travels in Kamchatka (pp.208-17). British Secretary of

State William Grenville wrote to Whitworth

enquiring as to whether Daikokuya could be recruited as an interpreter for

the embassy that was being organized to be sent to China and Japan

under

George Macartney.[60] The Russians prevented any

access to Daikokuya by Whitworth when he was brought to St.

Petersburg, and used him themselves as an interpreter in 1792 during the expedition to

Japan led by Adam Laxman,

as reported in

Lloyd's Evening-Post.

Although the Mulovsky expedition was postponed indefinitely in November 1787 due to the outbreak of war, the work done in preparing it was not without consequences. The reasons for sending out such an expedition remained cogent, and so Adam von Krusenstern’s plan in 1799 for a renewed effort met with a favourable reception, leading to the 1803-1806 expedition of the Nadezhda and Neva to the North Pacific under his command. Many of the tasks intended for the Mulovsky expedition were carried out by Krusenstern. During a subsequent voyage, from Kronstadt to Novo-Arkhangelsk, the Neva under the command of Lieutenant Ludwig von Hagemeister was the first Russian ship to visit Port Jackson, 16 June-1 July 1807.[61] Mulovsky’s name is commemorated by Cape Mulovsky in Terpeniya Bay on Sakhalin, named by Krusenstern, as he recorded:

In honour of my first commander in the

navy, the brave Captain Muloffsky, who, eighteen

years before, was chosen as chief of a great and important voyage of discovery,

which a hateful war (the Swedish affair), in which he himself gloriously

perished, prevented from taking place. He died on the 17th July, 1789, in the

battle near Bornholm (as commander of the Mstislaff, 74 guns), at the early age

of twenty-seven, it being my sad lot to witness his last moments.[62]

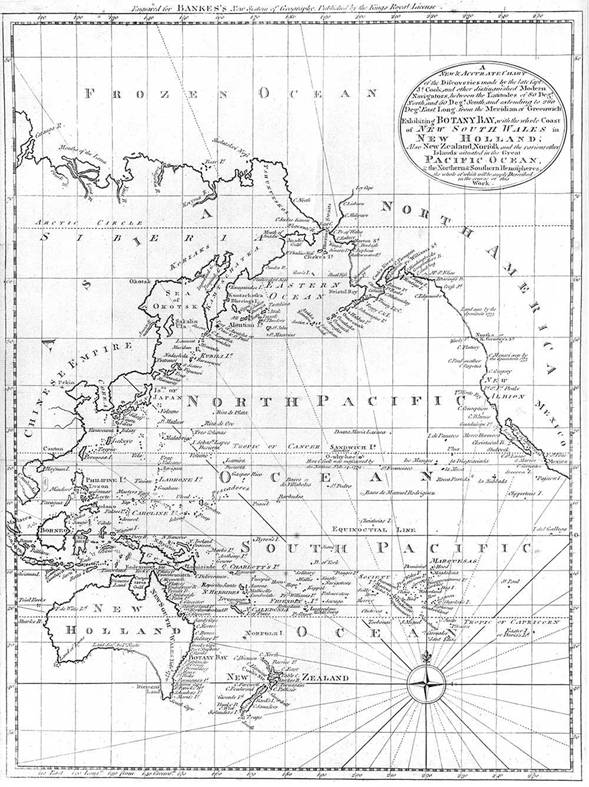

Thomas

Bowen, A New

& Accurate Chart of the Discoveries made by the late Capt. Js. Cook and

other distinguished Modern Navigators .... exhibiting Botany Bay, with the

whole Coast of New South Wales in New Holland, also New Zealand, Norfolk and

the various other Islands situated in the Great Pacific Ocean, & the

Northern & Southern Hemispheres, Bankes’s

New System of Geography, London, 1780.